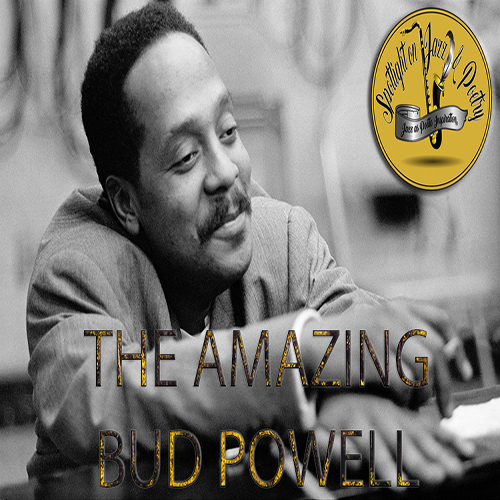

Earl “Bud” Powell (1924-1966) is generally considered to be the most important pianist in the history of jazz. Noted jazz writer and critic Gary Giddins, in Visions of Jazz, goes even further, saying that “Powell will be recognized as one of the most formidable creators of piano music in any time or idiom.”

The music of pianist Earl “Bud” Powell profoundly echoes a life that was unique in jazz history. Its daring, headlong improvisatory solos, often embedded in his stirring, original compositions, describe an arc of ecstasy and discord that his erratic private life closely limned. His name forever associated with the immediate-postwar, modernist movement, bebop, which challenged swing music, Powell nonetheless lived a life that no other musician ever had.

Born in Harlem in the midst of its cultural renaissance, and having taken formal lessons before he was six years old, he could mimic Fats Waller’s playing at age ten and was working professionally at fifteen. On record with a famous big band before he was twenty, by twenty-four he led his own trio on a number of record dates that put forward the progressive ideas defining piano modernism. His 1949 output stood beside that of alto saxophonist Charlie Parker, whose antisocial antics he matched offstage, and whose virtuosity he rivaled onstage.

But before Powell turned twenty-seven, his pre-eminence on his instrument notwithstanding, his erratic behavior got him involuntarily hospitalized–off the music scene for a crucial year and a half–just as bebop was gaining wide acceptance. (It was his third such confinement.)

Upon his release, he was welcomed back to his nightly piano-bench perch at the legendary nightclub, Birdland. Initially full of energy and eager to display his ideas–he was all but the house pianist there for 1953–his audiences soon began to turn from him, their having noticed his slurring of notes, which were accompanied by odd facial gestures and other tics.

But, again, his career arc proved to be unique: He didn’t flame out quickly or dramatically, as had Parker and another bebop genius whom he played alongside, trumpeter Fats Navarro. Powell’s decline was slow and intermittent and, after relocating to Europe in 1959, he played well often enough to fill nightclubs in Paris and Copenhagen for a few years.

This convinced Powell’s old manager to bring him back for a return engagement, at Birdland in fall 1964. His dissipations and illnesses, however, soon caught up with him again. So, though his career’s decline lasted two and a half times as long as had its peak, he was still only forty-one when he died, in Brooklyn, in 1966.